My Other Math Sites

Lessons From the Classroom

Giving Feedback With a Highlighter

I attended John Scammell's excellent 3-morning sessions on Formative Assessment at #TMC15. We were asked to share strategies that we may already be doing to give students feedback . I shared about how I used highlighters for this. I promised my group that I would write a short post about it, but I waited until now since I needed the school year to begin to have student samples to share.

I used highlighting to give my 6th graders feedback on their first PoW (Problem of the Week from The Math Forum).

It's challenging, as I hope all PoWs are, and even more so when it's the first one they get. I give no specific instructions on how they should write up their solution — nothing more than the usual "show all your work in order to receive credit." I want to see what raw stuff I get on this first submission. We'll worry about quality control soon enough.

I'm familiar with what I can expect with the first harvest of solution write-ups. One-fourth of the papers are pleasantly stellar, one-third show candid efforts (especially the ones with parents' writings on them), another third make me get up and stick my head in the fridge to find a cold-and-alcoholic beverage, and the rest of the papers remind me that some of my 6th graders are still working on finessing the opening of their combination locks.

Years ago I taught a writing elective. I was at the beach — at the Oregon coast — because that's where you should read and grade all writing papers. I forgot my red pen. I only had a yellow highlighter. The highlighter transformed my grading. I no longer cared so much about the writing mechanics — fuck spelling and punctuation and syntax. You got voice in your writing, kid. Your heart was wide open in this third paragraph. How did you know the rain smelled differently depending on what part of Portland you were in?

I highlighted sentences and words that spoke to me. I highlighted a brave sentence. I highlighted the weak ones also. The highlighter allowed me to interact with the kids' writings differently. I didn't add to or cross out anything they'd written. The highlighter didn't judge the same way my red pen was judging.

And that's the history of using the highlighter for me. But back to math. I have over 100 students and to write feedback for their bi-weekly PoW write-ups is all too time consuming. The different colored highlighters come to my rescue.

I'm going to continue using my binary scoring system because it worked well last year. I look through all the papers, separating them into two piles: papers that got it (full 10 points) and papers that fell short (1 point). These kids will get another week to revise their work and re-submit.

I use my yellow highlighter — just swipe it somewhere on their paper — to show that I'm having trouble understanding their work or that their work is lacking.

I use the pink highlighter to show that the answer is not clear, not specified, is partially or entirely missing.

I use another color (like green or blue) if the papers warrant another something-something that I need to address. I didn't need to with this week's PoW submissions.

If necessary, I will write on their papers directly. But I don't have to do too many of these because kids' mistakes, more often than not, are similar to one another.

When I pass the papers back, I tell students what each colored highlight means and what they need to do to revise their work, including coming in to get help from me. It's a helluvalot faster than what I used to do.

A Simpler Solution

I'm guessing this was about 5 years ago. I was at an all-day workshop when a high school math teacher, sitting next to me, asked about the PoW (from mathforum.org) that I had assigned to my students. I happened to have an extra copy in my backpack and gave it to her.

Dad's Cookies [Problem #2959]

Dad bakes some cookies. He eats one hot out of the oven and leaves the rest on the counter to cool. He goes outside to read.

Dave comes into the kitchen and finds the cookies. Since he is hungry, he eats half a dozen of them.

Then Kate wanders by, feeling rather hungry as well. She eats half as many as Dave did.

Jim and Eileen walk through next, each of them eats one third of the remaining cookies.

Hollis comes into the kitchen and eats half of the cookies that are left on the counter.

Last of all, Mom eats just one cookie.

Dad comes back inside, ready to pig out. "Hey!" he exclaims, "There is only one cookie left!"

How many cookies did Dad bake in all?

Maybe you'd like to work on this problem before reading on.

…

…

…

…

…

…

The teacher started solving the problem. She was really into it, so much so that I felt she'd ignored much of what our presenter was presenting at the time. She ran out of paper and grabbed some more. She looked up from her papers at one point and said something that I interpreted as I-know-this-problem-is-not-that-hard-but-what-the-fuck.

It was now morning break.

She worked on it some more.

By lunch time, she asked, "Okay, how do you solve this?" I read the problem again and drew some boxes on top of the paper that she'd written on. (Inside the green.)

She knew I'd solved the problem with a few simple sketches because she understood the drawings and what they represented. I just really appreciated her perseverance.

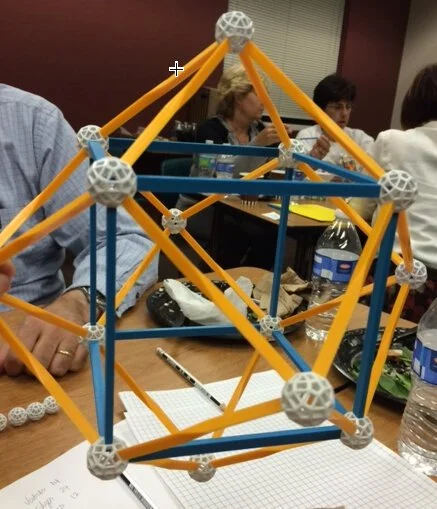

I share this with you because a few nights ago I was at our local Math Teachers' Circle where Joshua Zucker led us through some fantastic activities with Zome models. We were asked for the volume of various polyhedrons relative to one another. Our group really struggled on one of the shapes. We used formulas and equations only to get completely befuddled, and our work ended up looking like one of the papers above.

Over the years I've heard a few students tell me, "Mrs. Nguyen, my uncle is an engineer, and he can't help me with the PoW." Substitute uncle with another grown-up family member. Substitute engineer with another profession, including math teacher. I remember getting a note from one of my student's tutor letting me know that I shouldn't be giving 6th graders problems that he himself cannot solve. (The student's parent fired him upon learning this.)

I like to think that my love of problem solving will rub off on my kids. I hope they will love the power of drawing rectangles as much I do.