My Other Math Sites

Lessons From the Classroom

Good-Enough-for-Now Curriculum

I did my first webinar last week as a precursor to my talk at NCTM's Innov8 Conference next month. I thought it went okay — or horribly — just tough to be the only person with the mic and not being able to actually see the attendees. It was weird.

There are a few slides from the webinar that I'd like to share here mainly because I'm still thinking about them and writing anything down helps me set the wobbly gelatin.

Two weeks ago I presented at an independent school that's Preschool through Grade 8. Afterward, I was given a quick tour of the school — the 33-acre campus gleamed with pride in its thoughtful architecture, manicured grounds, state-of-the-art this and that, and a smorgasbord of elective offerings, including Mandarin and photography.

My school is Kindergarten through Grade 8, and the similarity between my school and this independent school pretty much ends there. I teach four classes, my smallest class has 23 8th graders, the other three, all 6th graders, have 32, 35, and 36 students. We're a Title 1 public school.

I bring up the private school and my public school because, like apples and pomegranates, they are quite different. So, when we do PD and share whatever it is that we share about education and serving children, we need to be mindful about the space that each teacher occupies in her building and be mindful about the children who come into that space.

When someone shares something with me, one or more of these thoughts cross my mind: 1) I can see how that would work with my students, 2) I can see how I might adapt this to fit my kids, 3) This person is afraid of children or unaware that children are people, 4) Nobody cares.

Likewise, when I have the stage to share, I'm assuming you have similar thoughts of my work. But I beg you to think about the space that I share with my students.

Below is a quasi rating scale of "critical thinking demand" that I'd created to place the types of tasks that I regularly give to my students. And this scale is only possible because I'm mindful of the tasks' contents and my own pedagogical content knowledge to facilitate these tasks.

What are these six things? The resources for these are on this spreadsheet.

1 & 2. Assessment and Textbook: We're using CPM. [04/07/2022: We now use Open Up Resources and Desmos.]

3. Warm-up: Due to our new block schedule, we've only been doing number talks and visual patterns.

4. Problem-of-the-Week

5. Task

6. PS (Problem Solving)

Do these 6 things align to the curriculum?

The slide below shows the 4 types of tasks that are aligned to the curriculum, or that when I pick a PoW or Task, I make sure it correlates to the concepts and skills that we're working on in the textbook. Therefore, it's entirely intentional that the warm-up and PS are not aligned because critical thinking and creative thinking are not objects that we can place in a box or things that I can string along some prescribed continuum.

All 6 types of tasks are of course important to me. I try to implement them consistently with equal commitment and rigor to support and foster the 8 math practices.

Which ones get graded?

I don't grade textbook exercises, i.e., homework, because I can't think of a bigger waste of my time. I post the answers [in Google Classroom] the day after I assign them. I don't grade PS because that's when I ask students to take a risk, persevere, appreciate the struggle. I don't grade warm-up because I don't like cats.

I'm finally comfortable with this, something I've been fine-tuning each year (more like each grading period) for the last 5 years. I could be a passive aggressive perfectionist — or just an asshole when it comes to getting something right — so it's no small admission to say that I'm comfortable with anything.

It's about finding a balance, an ongoing juggling act between building concepts and practicing skills, between problem-posing and answer-getting, between teacher talk and student talk, between group work and individual work, between shredding the evidence and preserving it. Then ice cream wins everything.

Here's the thing. We want to build a math curriculum that makes kids look forward to coming to class everyday. I trust that that's true for more than half of my students — this could mean anywhere between 51% and 80%. I think we're doing something wrong when kids look forward to just Measurement Monday, Tetrahedron Tuesday, or Function Friday. Math should not be fun only when students get to play math "games"!

Giving Feedback With a Highlighter

I attended John Scammell's excellent 3-morning sessions on Formative Assessment at #TMC15. We were asked to share strategies that we may already be doing to give students feedback . I shared about how I used highlighters for this. I promised my group that I would write a short post about it, but I waited until now since I needed the school year to begin to have student samples to share.

I used highlighting to give my 6th graders feedback on their first PoW (Problem of the Week from The Math Forum).

It's challenging, as I hope all PoWs are, and even more so when it's the first one they get. I give no specific instructions on how they should write up their solution — nothing more than the usual "show all your work in order to receive credit." I want to see what raw stuff I get on this first submission. We'll worry about quality control soon enough.

I'm familiar with what I can expect with the first harvest of solution write-ups. One-fourth of the papers are pleasantly stellar, one-third show candid efforts (especially the ones with parents' writings on them), another third make me get up and stick my head in the fridge to find a cold-and-alcoholic beverage, and the rest of the papers remind me that some of my 6th graders are still working on finessing the opening of their combination locks.

Years ago I taught a writing elective. I was at the beach — at the Oregon coast — because that's where you should read and grade all writing papers. I forgot my red pen. I only had a yellow highlighter. The highlighter transformed my grading. I no longer cared so much about the writing mechanics — fuck spelling and punctuation and syntax. You got voice in your writing, kid. Your heart was wide open in this third paragraph. How did you know the rain smelled differently depending on what part of Portland you were in?

I highlighted sentences and words that spoke to me. I highlighted a brave sentence. I highlighted the weak ones also. The highlighter allowed me to interact with the kids' writings differently. I didn't add to or cross out anything they'd written. The highlighter didn't judge the same way my red pen was judging.

And that's the history of using the highlighter for me. But back to math. I have over 100 students and to write feedback for their bi-weekly PoW write-ups is all too time consuming. The different colored highlighters come to my rescue.

I'm going to continue using my binary scoring system because it worked well last year. I look through all the papers, separating them into two piles: papers that got it (full 10 points) and papers that fell short (1 point). These kids will get another week to revise their work and re-submit.

I use my yellow highlighter — just swipe it somewhere on their paper — to show that I'm having trouble understanding their work or that their work is lacking.

I use the pink highlighter to show that the answer is not clear, not specified, is partially or entirely missing.

I use another color (like green or blue) if the papers warrant another something-something that I need to address. I didn't need to with this week's PoW submissions.

If necessary, I will write on their papers directly. But I don't have to do too many of these because kids' mistakes, more often than not, are similar to one another.

When I pass the papers back, I tell students what each colored highlight means and what they need to do to revise their work, including coming in to get help from me. It's a helluvalot faster than what I used to do.

A Simpler Solution

I'm guessing this was about 5 years ago. I was at an all-day workshop when a high school math teacher, sitting next to me, asked about the PoW (from mathforum.org) that I had assigned to my students. I happened to have an extra copy in my backpack and gave it to her.

Dad's Cookies [Problem #2959]

Dad bakes some cookies. He eats one hot out of the oven and leaves the rest on the counter to cool. He goes outside to read.

Dave comes into the kitchen and finds the cookies. Since he is hungry, he eats half a dozen of them.

Then Kate wanders by, feeling rather hungry as well. She eats half as many as Dave did.

Jim and Eileen walk through next, each of them eats one third of the remaining cookies.

Hollis comes into the kitchen and eats half of the cookies that are left on the counter.

Last of all, Mom eats just one cookie.

Dad comes back inside, ready to pig out. "Hey!" he exclaims, "There is only one cookie left!"

How many cookies did Dad bake in all?

Maybe you'd like to work on this problem before reading on.

…

…

…

…

…

…

The teacher started solving the problem. She was really into it, so much so that I felt she'd ignored much of what our presenter was presenting at the time. She ran out of paper and grabbed some more. She looked up from her papers at one point and said something that I interpreted as I-know-this-problem-is-not-that-hard-but-what-the-fuck.

It was now morning break.

She worked on it some more.

By lunch time, she asked, "Okay, how do you solve this?" I read the problem again and drew some boxes on top of the paper that she'd written on. (Inside the green.)

She knew I'd solved the problem with a few simple sketches because she understood the drawings and what they represented. I just really appreciated her perseverance.

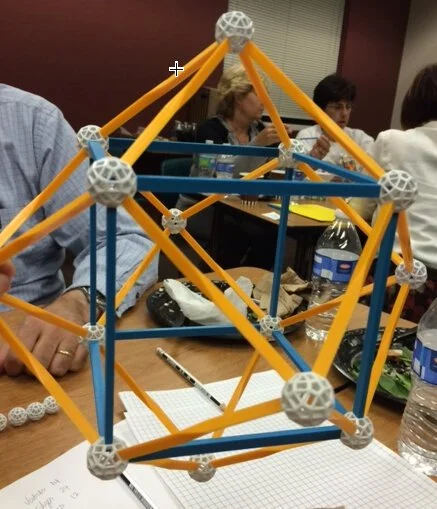

I share this with you because a few nights ago I was at our local Math Teachers' Circle where Joshua Zucker led us through some fantastic activities with Zome models. We were asked for the volume of various polyhedrons relative to one another. Our group really struggled on one of the shapes. We used formulas and equations only to get completely befuddled, and our work ended up looking like one of the papers above.

Over the years I've heard a few students tell me, "Mrs. Nguyen, my uncle is an engineer, and he can't help me with the PoW." Substitute uncle with another grown-up family member. Substitute engineer with another profession, including math teacher. I remember getting a note from one of my student's tutor letting me know that I shouldn't be giving 6th graders problems that he himself cannot solve. (The student's parent fired him upon learning this.)

I like to think that my love of problem solving will rub off on my kids. I hope they will love the power of drawing rectangles as much I do.